The Ottoman Sultanate (1299-1922 as an empire; 1922-1924 as caliphate only), also referred to as the Ottoman Empire, written in Turkish as Osmanlı Devleti, was a Turkic imperial state that was conceived by and named after Osman (l. 1258-1326), an Anatolian chieftain. At its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries, the empire controlled vast stretches including Anatolia, southwestern Europe, mainland Greece, the Balkans, parts of northern Iraq, Azerbaijan, Syria, Palestine, parts of the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, and parts of the North African strip, in addition to the major Mediterranean islands of Rhodes, Cyprus, and Crete. Renowned the strongest military superpower of its time, the empire stagnated and faced prolonged decline from the late 16th century CE onwards until it was replaced by the modern Republic of Turkey after the First World War (1914-1918).

Rise, Zenith & Fall of the Ottoman Empire

In the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks, a people from the Asian steppe who had accepted the Sunni version of Islam, swept over Persia and neighboring eastern territories and then advanced westwards towards Anatolia. There, they dealt the imperial forces of the Byzantine Empire (330-1453) a devastating defeat near Manzikert in 1071, and henceforth several Turkic tribes settled the region. By the end of the 13th century, the various Anatolian beyliks (petty kingdoms) were virtually independent but feuding amongst each other. Osman (r. 1299-1326), the bey (chieftain) of Bithynia, a region situated westwards, near the Sea of Marmara, initiated a war with the bordering Byzantine realm, expanding his domains at their expense and laying siege to Prusa (Bursa) which fell after his death in 1326.

Osman's successors swept over the Byzantine holdings in Anatolia and Europe, even taking over the Balkans by the close of the 14th century. The Europeans made vehement attempts to fight off the Ottomans but they failed, most notably at the pivotal battles of Kosovo (1389) and Nicopolis (1396). The Turks met their match, not from the west but the east, when they clashed with the rival Timurid forces (over a territorial conflict in Anatolia) under the Turko-Mongol leader Timur (aka Tamerlane, r. 1370-1405) near Ankara in 1402. The Ottomans were defeated, and Sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402) was captured.

However, the western powers failed to exploit this opportunity to its fullest, and after a civil war, otherwise known as the Ottoman Interregnum (1402-1413), Mehmed I (r. 1413-1421), a son of Bayezid, emerged victorious as the unrivaled ruler of the unified Ottoman realm, and for this, he is often dubbed as the second founder of the empire. Having restored the empire's borders as they were before the Battle of Ankara, the Ottomans appeared before the legendary Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, the last bastion of the Byzantine Empire, in 1453, under Mehmed II the Conqueror (r. 1451-1481, a grandson of Mehmed I).

The Ottomans turned eastwards under Selim I (r. 1512-1520, Mehmed the Conqueror's grandson) who targeted the rival Safavid (Shia) Dynasty of Iran (1501-1736) and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517). He dealt a pulverizing defeat to the former in 1514 but did not pursue a complete conquest; the Mamluk realm, however, was engulfed in its entirety by 1517.

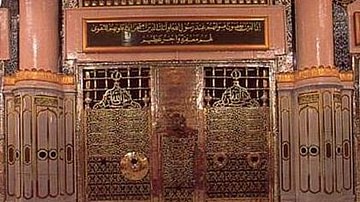

The latter victory gave the Ottomans access to the Islamic holy cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, allowing them to claim the title of Caliph of the Islamic world. The Ottomans and Safavids, and successive Persian empires, would continue to clash intermittently for the next three centuries, and the territories in Iraq and Azerbaijan would exchange hands several times until the matters were finally resolved with a peace treaty in 1847.

Selim's son Suleiman I (r. 1520-1566) remains the most celebrated ruler of the Ottoman era and is referred to as Kanuni (Lawgiver) in the east and the Magnificent in the west. He conquered Belgrade in 1521, took the island of Rhodes in 1523, and secured a major and consequential victory against Hungary at the Battle of Mohács in 1526 (which destabilized the region for years to come, and allowed the Turks to assert their dominion over it, competing the Austrians in doing so). In Africa, Algiers had accepted Selim's suzerainty in 1517, and Tunis entered Ottoman rule under Suleiman in 1534.

This territorial loss was merely a prelude for a century-long episode to come. The Tatars of Crimea were defeated by the Russians in 1783, hence cutting off the empire's hegemony in the Eastern Black Sea region. The Greek Revolution (1821-1829) established Greek independence, and their example was followed by Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania, all of whom broke away from the empire by the end of the 19th century CE. Egypt escaped direct Ottoman control as early as the 1830s and was eventually lost for good to the British Empire five decades later in the 1880s. France seized Algeria in 1830 and Tunis in 1881, and the last Ottoman-held African territory, Libya fell to Italy in 1911.

The last autonomous Ottoman ruler to have made any significant contributions to the empires was Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876-1909) who took the scepter amidst the First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire (1876-1878; an era of constitutional monarchy), which he put an end to in just two years, reasserting absolute monarchical control. Hamid made vehement attempts at modernization (most notably in the education sector) and introduced several technological advancements such as laying down extensive railway systems but remains controversial due to his involvement in the massacre of local Armenian population (1894-1896; also known as the Hamidian massacres), which are often seen as a prelude to the Armenian genocide (1914-1923) that happened later on.

Abdul Hamid was deposed in 1909 by the Young Turks party, a nationalistic and secular political entity which restored constitutional monarchy in the empire, also known as the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire (1908-1920). However, from that point onwards, the sultans became mere figureheads and the empire had started on the course of its destruction. The final nail was struck in the coffin of the empire when it became involved in the First World War (1914-1918) on the Central Powers' side (Austro-Hungarian Empire and Germany). The Sultanate was destroyed by the war and officially ceased to exist by 1922.

In the aftermath of the war, the Greek army invaded Anatolia, taking Smyrna (Izmir) and moving inland. The Greek invasion force was pushed back by Turkish freedom fighters, led by the Turkish nationalist leader and the founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal (r. 1923-1938), during what was later termed as the Turkish War of Independence (r. 1919-1923). The last Ottoman leader, Abdulmejid II (r. 1922-1924) served only as the Caliph of Islam (symbolically) for two years, until the office was officially abolished by Kemal.

Ottoman Government

From the time of Murad I (r. 1362-1389), the leader of the Ottoman State was called sultan, often understood as a religiously inspired warrior king. The title of the sultan was used by several monarchs of the Islamic world in medieval times, and in many cases, further legitimized by the blessings of the spiritual leader of the Muslim community, the caliph (Khalifa in Arabic). The sultan, though in theory a subordinate to the caliph, was practically independent and in most cases more authoritative.

The sultan's actions and decisions were considered final, although there was an advisory body of viziers (ministers; also known as paşa or pasha) to assist, and in times even replace the sultan in political affairs. These ministers and several other high-ranking bureaucrats were selected from promising officers of the elite Jannisary military corps conscripted from the conquered Balkans territory. The grand vizier (prime minister) was the direct subordinate of the sultan and in many cases proved instrumental in asserting the latter's authority, as exemplified by the members of the Köprülü family who served the office in succession from 1656 to 1703.

Although the sultan was the unrivaled ruler of the realm, the Ottomans allowed local rulers to retain their autonomy in return for fealty, and in several cases, the locals would retain their system of governance, such as in the Balkans. The Ottoman administrative framework can be perfectly surmised from the following extract:

Paradoxically the early Ottoman state was both militantly Islamic and strongly influenced by Greek culture, heir to the Saljuqs (Seljuks) but also to practices and structures derived from the Roman-Byzantine Empire it replaced. Straddling the Christian Balkans and the western reaches of Dar al-Islam, it was a bridge between rival civilizations. (Ruthven, 86)

The biggest flaw in the Ottoman sovereignty framework was that of succession; the Ottomans followed somewhat of a Darwinian principle: only the most capable prince could take the throne. The princes, known as Şehzade, were expected to serve as governors of various regions under their father's suzerainty to gain military and administrative experience, however, this practice was forsaken in later years, as it created competition for a claimant and hence invited fratricide.

From the time of Selim II (r. 1566-1574), as the sultans submitted to the pleasures of the harem and distanced themselves from the administration of their realm, corruption, intolerance, and nepotism began to plague the framework. Potential successors were left inept without any practical experience, allowing other parties (ministers, janissaries, or queens) to assert more control over the sultan, who then became pawns in palace intrigues. For a brief period in the 17th century CE, mother queens (Valide Sultan), began asserting direct control over minor sovereigns, as exemplified by the rule of Kosem Sultan (r. 1623-1632 & r. 1648-1651), after the death of her husband, Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617).

Later sultans made vehement attempts to solidify the empire, and Sultan Abdulmejid I (r. 1839-1861) introduced a list of important reforms known as the Tanzimat (1839-1876; originally conceived by his father Mahmud II). These reforms offered many rights such as equality and religious tolerance for all while also overhauled the financial structure of the empire, promoted Ottoman nationalism in contrast to ethnic divisions, limited the role of unruly factions, and undermined the authority of all anti-state conspirators.

However, secular nationalists were unimpressed by the Tanzimat reforms and wished to create a more European-style government. They gave rise to the First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire (1876-1878) which lasted only for the first two years of Abdul Hamid's reign. There was no party system but the elected members of the Ottoman parliament were deemed as the representatives of the people and asserted some degree of control over the Sultan until he put an end to the era.

Hamid, who was opposed to liberal reforms, was deposed in 1909, and hence the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire (1908-1920) commenced. This time around, the sultans became mere figureheads placed by the ruling pashas (ministers), who took over the reins of power, most prominently the trio that served amidst the First World War, namely Mehmed Talat Pasha, Enver Pasha, and Ahmed Cemal Pasha of the Young Turks party, also known as the “Three Pashas” (and who are considered responsible for the Armenian Genocide of 1914-1923).

Religion

Islam remained a defining factor for the empire; the sultan was expected to protect the people of that faith and Islam itself - blasphemous remarks were not tolerated. However, as historian Stephen Turnbull comments,

...the Christians under Muslim rule seem to have enjoyed a greater toleration than was shown to the Orthodox under Latin domination, so resistance was not always as fierce as may have been assumed. Churches might be turned into mosques, while those left in Christian hands suffered certain restrictions such as at the prohibition of bell ringing and public processions, but matters could've been much worse. The Orthodox world had the tragic memory of the Fourth Crusade of 1204 CE to remind them of how well off they were under Ottoman rule by comparison with a western conquest. 'Better the Sultan's turban than the bishop's mitre' wrote one Byzantine scholar. (75-76)

An instance of religious inclusion and acceptance can be stated from the time of Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512) who welcomed the Spanish Jews in 1492, in stark contrast to the mistreatment of Jews rampant throughout medieval Europe. Mehmed the Conqueror went so far as to write a declaration offering the Christian clerics complete protection and religious independence.

However, instances of extremism and intolerance on religious, ethnic or nationalistic basis also abound the annals of Turkish history such as the violent butchery of war captives pioneered by Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402) after the Battle of Nicopolis (1396), the plundering of conquered cities, and the maltreatment and genocide of local Armenians from the late 19th to early 20th century.

Ottoman Military

The founder of the empire, Osman, branded himself as a ghazi, meaning holy warrior, and led forces majorly composed of such holy warriors, waging ġazā, a form of holy war, against the Byzantines. As the Ottoman realm expanded, new military corps were incorporated into the growing Turkish army. Raider cavalry called the akincis (akin - raid) was often employed to scout and launch preemptive raids in the enemy's territory before the main army arrived. The sipahis were the elite Ottoman heavy cavalry units, well-armored and equipped with lances, who were paid with land instead of salaries.

The light infantry was mostly composed of irregular azap(s) (meaning unmarried or bachelor, which they were), who were equipped with both melee and ranged weapons. However, the most iconic Ottoman (heavy) infantry units were recruited via the devşirme (meaning child levy) system, laid down by Sultan Murad I, by which children from the Balkans were conscripted, converted to Islam and trained as elite janissary soldiers (Turkish: yeñiçeri, meaning new soldier), some of whom would also serve as ministers and leading bureaucrats of the realm.

The janissaries served as both heavy infantry and cavalry units, although they are mostly famous for the former. Their resilience and skill won them the admiration and dread of European powers, for instance, they were largely responsible for the Ottoman victory against a European Crusader coalition army at Varna (1444). The janissaries were innovative in that they wore official uniforms and were equipped with gunpowder weapons like arquebuses, which often helped them turn the tide of battle.

The Ottomans were famous for the incorporation of gunpowder weapons, including light and heavy cannons; the latter being exemplified by the massive Dardanelles Gun (Şahi topu), a prototype of which was also deployed before the walls of Constantinople in 1453. The Ottoman army also pioneered the use of an official military band, known as the mehterân, who played war tunes (and several imperial anthems) of which many songs are famous even to this day.

This military structure, though initially quite successful, gradually eroded as no attempts were made at modernizing or reforming the forces. The janissaries ascended the power ladder, at the expense of the sultans, alienating other military orders, which took to brigandage, such as the Celali revolts (1590-1610; named after an early albeit unrelated Shia rebel) that raged throughout the empire's core and took decades to completely subdue. Meanwhile, external foes started gaining a military edge. Selim III (r. 1789-1807) introduced the Nizam-i-Cedid (New Order), a reformed military system, which could potentially replace the obsolete janissaries. This move was met with stiff resistance by the janissaries, who forced the sultan to abandon his efforts and ultimately took his life.

Mahmud II (r. 1808-1839) realized that the survival of the fragmenting empire could only be preserved with a new army, and he thenceforth set upon emulating Selim's example. He trained modern troops, who pledged absolute loyalty to the house of Osman, and in turn, these soldiers destroyed the janissaries when they rebelled, reasserting the sultan's authority in 1826. They were branded as Asakir-i Mansure-i Muhammediye (The Victorious Soldiers of Muhammad), often shortened as Mansure Army (Victorious Army).

The Ottomans were also famous for valuing talent, even in their enemies, for instance, they recruited corsairs and pirates, who raided their ships, amidst their ranks, turning foe into a friend. Two of most notable examples are that of Hayreddin Barbarossa (l. 1478-1546), the victor of the naval battle of Preveza (1538), and Yusuf Raïs (l. 1553-1622), originally named Jack Birdy, and possibly the inspiration for Captain Sparrow's character in the Pirates of the Caribbean series. The Ottoman navy, which was first commissioned on a titanic scale by Suleiman the Magnificent, dominated the Mediterranean, in rivalry to other European naval powers, most notably Venice, until its defeat at the Battle of Lepanto (1571). The vestiges of Ottoman naval power waned from the 17th century onwards due to the friction in modernization and lack of funds to support a stronger and bigger fleet.

Economy & Trade

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 was not only the start of advanced Ottoman imperial ambitions but also secured trade domination of the area for the Turks. Since the Tatars of Crimea had sworn fealty to the sultan, Mehmed II also held the hegemony in the Black Sea area. With the Dardanelles under their control, the Turks closed the historical Silk Road for their western foes. Exclusive trade rights with Mughal India (r. 1526-1857, intermittently), a regional superpower, via the Indian Ocean also brought in heaps of revenue for both empires, and the European merchants who did use the Ottoman-controlled routes were bound to pay taxes to the empire.

Ottoman hegemony in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, and their control of the Dardanelles, forced rival European powers to seek new trade routes, westwards, into the New World. However, the Turks soon lost that edge in the east, as explained by historian Mehrdad Kia:

The economic and financial decline of the empire was exacerbated by the significant diversion of trade from traditional land routes to new sea routes. Historically, the vast region extending from Central Asia to the Middle East served as a land bridge between China and Europe. The taxes and the custom charges collected by the Ottoman government constituted an important component of the revenue generated by the state... The Portuguese rounding of the Cape of Good Hope and subsequent establishment of a direct sea route to Iran, India, and beyond, however, allowed European states and merchants to bypass Ottoman held territory... (12)

Ottoman Era Art & Architecture

Architectural masterpieces from the Ottoman era have dazzled and mesmerized visitors for centuries. The Ottoman architecture draws heavily from Persian, Byzantine, and Arabic styles, intermingling the three to create a unique blend, perfectly embodied in their designs for masjids or mosques of which several were commissioned by the sultans as they are central to the Islamic belief. Madrassas (religious schools), soup kitchens, hospitals, universities, sultans' tombs are also perfect examples of Turkish architectural mastery.

Ottoman palaces like the Topkapi (meaning Cannon Gate) which served as the imperial housing and headquarters between the 15th and 16th centuries, and the Dolmabahçe (meaning (Filled-in Garden) which replaced the former in mid-19th century, are also great examples of architectural excellence from the era, although the latter is also an example of the toxic largess that crippled the empire's economy.

Ottoman era art adorns the pages of several manuscripts commissioned by the sultans. The style, as with the architecture, has been adopted from neighboring cultures. Several miniatures, Islamic calligraphic masterpieces, decorative carpets, tiles, and portraits from the era provide a peek into the cultural values and history of the nation. The sultan's name was also written in a stylized fashion, known as the tughra which was used to sign imperial documents. Poetry and music were also patronized by the Ottoman rulers, many of whom were excellent composers themselves; Suleiman the Magnificient would often write romantic verses for his wife Hurem Sultan (l. c. 1502-1558), under the pen name Muhibbi (meaning lover).

From the 19th century onwards, European-style music was also inculcated in the court, as exemplified the official Ottoman Imperial Anthem, composed under the patronage of Sultan Abdulmejid I (r. 1839-1861). These forms of art and architecture allow modern observers to better understand the things that the Turkish people held close to their hearts, and although European influences can be observed in gradual increments over the centuries, one can still distinguish the elements that made the Ottoman Turks unique.